By: Allison Pfingst

Reading Group Participant

Administrator and Advisor, Fashion Studies Program

Connection is a word that has come to take on tremendous meaning during the COVID-19 crisis. We are increasingly worried both about the effects that a lack of internet connection and of personal connection may have on ourselves and our students, as this pandemic shows few signs of slowing down.

Yet as we face these serious concerns about the tenuousness of our connectivity, I am seeing it grow and strengthen before my eyes. It is taking new and meaningful forms that I believe, if we maintain them, will make Fordham stronger and more flexible than it has ever been.

Faculty are taking on the work of colleagues that are facing the challenges of full-time quarantine childcare. Father McShane’s thoughtful prayers, that he sends out via email, provide comfort to us all, regardless of faith. Professors who struggled to turn on their classroom projectors are now Zooming regularly with their students.

Every single member of the Fordham community has been thrust outside of his/her comfort zone. And every single member of the Fordham community is compassionately working across all boundaries of department, office, and position to ease these transitions on us all for the greater good.

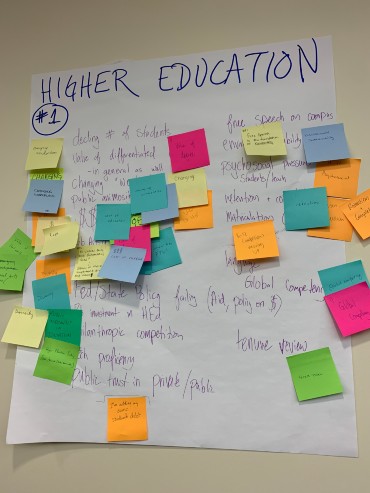

If we can maintain that openness and solidarity and direct it towards the ideas that are forming in the ReIMAGINE Higher Education groups, there is truly no limit to what we can accomplish. Interdisciplinary programs that are funded, nimble, and fully supported by the departments? Easy. Food and housing security for all of our students? A no brainer. Courses that integrate the work of our fabulous Student Services teams? Of course! All of it is possible if we continue to work together in the way that we have during this crisis.

That’s a tall order.

It’s a little lofty.

It’s a little beyond the call of a school or a workplace.

It verges on preachy.

But that’s exactly what I’ve always loved about Fordham. It has always challenged its community to go further. It has never been enough to just be a good student or a good employee. Fordham expects you to be a good person, a man or woman for others.

2020 is a new world that will require a new education, and I’m looking forward to watching how the Fordham community takes on that challenge together.