By: Christopher Gu

Reading Group Participant

Director of Academic and Financial Operations

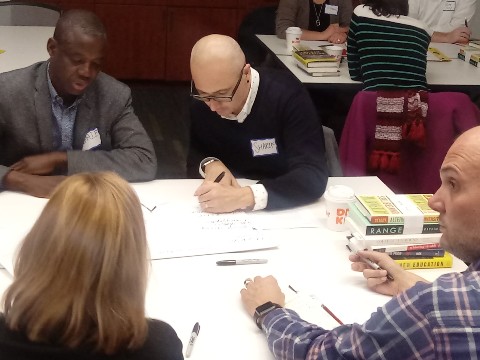

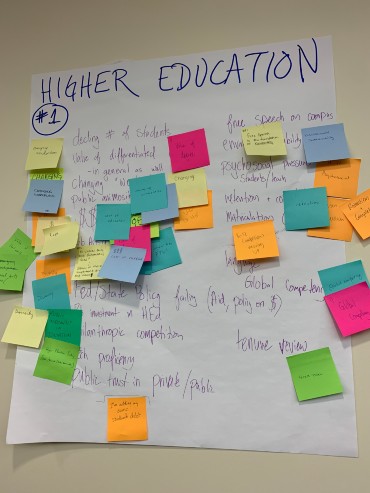

In the first part of the ReImagine HigherEd Speaker Series, we were lucky enough to have Dr. Cathy N. Davidson, author of The New Education, speak to a packed house in Bepler Commons last Tuesday. Davidson, the Founding Director of The Futures Initiative at the CUNY Graduate Center, spoke about how crucial it is to revolutionize the current higher education model, which is simply not sustainable with rapid technological and generational shifts. This is the focal point of the work that both the ReImagine HigherEd Reading Group and the Incubator Group are doing this semester.

Davidson divided her presentation into three parts: Inheritance, Disruption, and Restructuring. The current model of higher education still bears many of the ideas that Charles Eliot, Harvard’s longest serving president in the late 19th Century, outlined in his own manifesto, the original The New Education. This rise of higher education coincided with the shift from an agricultural to an industrial society. Many of the ideas, such as the A-F grading system, majors and minors, credit hours, and multiple-choice examinations were all born out of this era. We have essentially inherited these rituals, without making much advancement over a century later.

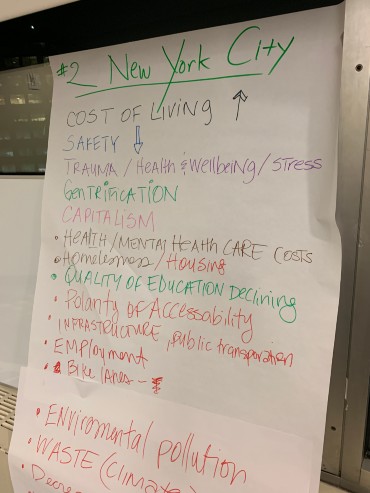

With the rising cost of college, the heavy burden of student debt, and increasing technological advances, it is imperative to disrupt the traditional model of higher education in order to make college more accessible and relevant. We have talked in the ReImagine HigherEd Reading Group about how a college education needs to prepare students for careers that may not even exist yet!

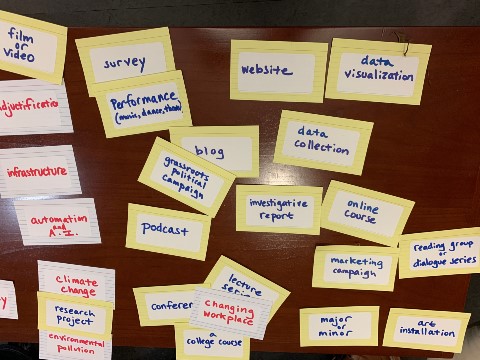

Davidson talks about how equality must be at the core of the new structures that we design. She challenges us to think about restructuring the academic reward system. What if research, teaching, and service were all weighted equally? For students, how can we structure the curriculum for more active learning and participation? Davidson, who has spearheaded interdisciplinary programs at both Duke University and CUNY, believes that the STEM subjects and the liberal arts can go hand-in-hand in the classroom. Learning does not have to be limited to the singular subject matter; in real life, problems cut across multiple disciplines and students need to be able to think critically and holistically.

Having just finished reading Cathy N. Davidson’s book and after seeing her presentation, I could not agree more with the urgency of which this work of reimagining and restructuring needs to be done. In The New Education, Davidson spotlights the work that specific colleges are doing to advance higher education and I look forward to the work that our own ReImagine groups will be producing in the coming months to share with the rest of the Fordham community.