By: Edward Dunar

Incubator Participant

Graduate Teaching Fellow and Doctoral Student

The past several weeks have been a blur. When Fordham announced its switch to online learning in response to the COVID-19 crisis, I had a plan ready, but implementing it in my (now virtual) classroom has offered an ongoing series of reminders that there is still much that I need to learn. Throughout, I’ve been impressed by the flexibility, nimbleness, and creativity of my students and colleagues. We’re all making lots of mistakes, but we’re rising to the occasion.

As we work as quickly as we can to adjust, many of us feel the weight of systems ripe for reform. The disruption in the middle of the semester and the subsequent decision of many universities to switch to alternative modes of grading raises questions about the effectiveness and equity of our methods of evaluation in “normal times.” In navigating how to send students back home as safely as possible, we encounter the challenges faced by students who don’t have a place to go. As we switch to online instruction, we notice the often-reductive assumptions and philosophies of learning baked into many of the platforms and technologies to which we now must turn.

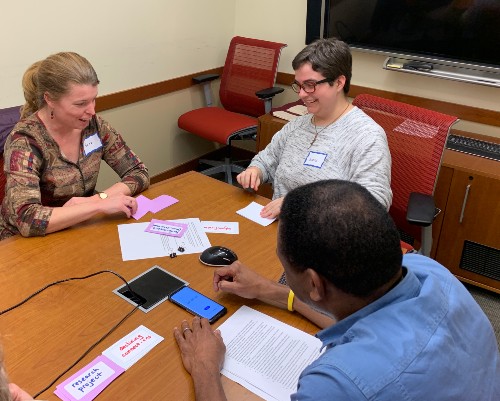

As I try to hold together short-term urgency with long-term hope, I’ve found inspiration in the design thinking that we employ in our Reimagining Higher Education Incubator. The beauty of this approach to me is that the emphasis is on ongoing perception, experimentation, and adjustment rather than controlling all aspects of how our work will unfold. Design thinking shifts us away from asking, “How can I make sure everything goes according to plan?”, and instead leads us to focus on the needs of the people and communities to which we are responsible, look for opportunities for adjustment, and build on what works. It serves as a middle ground between acting reactively and feeling bound to overly-specific plans. It calls for an ethic of observation, adaptation, and accountability in our practice of the craft of teaching.

I find this approach clarifying and freeing as I move forward in my own work in the face of new demands. Our main responsibility now is the safety of our communities. We adjust as needed according to our values in response to new circumstances. Some of the experiments we try now might scale up after the crisis is over. Some of our experiences now might give us insight into persisting problems that need long-term solutions. Other experiments won’t work or will turn out to be temporary measures only. We will learn from triumphs and missteps alike. The key will be to center ourselves in practices of attentiveness and iteration that will keep us committed to what is most important—the well-being and growth of our students.